I was told by a friend that Councilor DeBoer had a website up on the Internet for his 2015 re-election campaign. After some searching, I came across Our Rent Is Too Damn High. Sadly, the web site has been suspended from Ghost.io, but luckily there was a cached version of it. This one is from March 11th, 2015.

One area of concern is Councilor DeBoer’s painting of the development and rent problem in West Lafayette: City Council along with a confederation of long-term residents have exercised their political interest to limit where, when, and how new development occurs. The rise in rents can be traced to the regulations imposed by these interest groups intended on thrwarting [sic] density in the name of postarity [sic].

Councilor DeBoer, I can assure you that there is more at play here than the City Council (does the Mayor sit idly by?) and a confederation of long-term residents. I look forward to working with you Councilor, on shedding light on these other forces and interest groups in our community.

A question that I have asked for a couple of years now: Why there isn’t more of a focus along the Southern side of West Lafayette in terms of densification?

Instead, we have 5 or 6-story buildings cramping 3-story buildings in the historic Village of Chauncey, a 6-story building in a residential neighborhood, and countless cases of sprawl.

If there was less emphasis on changing the northern corridor along Northwestern, which abuts New Chauncey, Northwestern Heights, etc. there would be more of a celebration by the confederation I am sure.

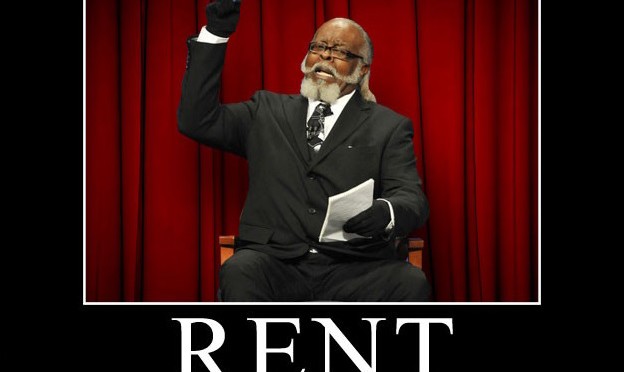

Our Rent Is Too Damn High

Why it’s a problem. How we can fix it together.

The Problem

These interest groups insist that no building be taller than a few stories, they demand that every structure meet an arbitary parking quota. Over time, this has caused an imbalance in the negotiating power between the customer and the rentier class. With insufficient stock, landlords are free to extort you into renewing a lease before you have the opportunity to unpack. So now we live under an omnipresent anxiety that the best places to live for our budget will soon be off the market. When too few ideal dwellings exist, it’s a sellers market. We deserve better as a community. We are owed a leveling of the playing field.

The Solution

The market knows more people want to live here than we can currently fit. It’s why we are treated to flashy shows and detailed drawings about proposals for new buildings throughout the year. But these developers are always playing toward the sensibility of legislators who aren’t suffering under the economic pain of exorbitant rents. We must fix that, together. And we can.

The Councilor

I have called West Lafayette home since arriving in 2006. I graduated from Purdue in 2011 with degrees in political science and history, and now work in Marketing. I love this city, its people and its culture. Yet I am not content with the status quo.I have been fighting to reduce the cost of living and improve our community since I assumed office in August 2014. Serving the residents of District 1 is the privilege of a lifetime. One that comes with a responsibility to ensure the interests of student residents are balanced against entrenched landlords and the overbearing influence of neighborhood groups.I want us to have more bars, offices, restaurants, and affordable apartments. I want us to maintain a close and responsible relationship with our community. That includes maintaining a relationship with law enforcement that has made our community safe, while also preventing unnecessary non-violent arrests that can damage careers and opportunities for decades after graduation.

I have called West Lafayette home since arriving in 2006. I graduated from Purdue in 2011 with degrees in political science and history, and now work in Marketing. I love this city, its people and its culture. Yet I am not content with the status quo.I have been fighting to reduce the cost of living and improve our community since I assumed office in August 2014. Serving the residents of District 1 is the privilege of a lifetime. One that comes with a responsibility to ensure the interests of student residents are balanced against entrenched landlords and the overbearing influence of neighborhood groups.I want us to have more bars, offices, restaurants, and affordable apartments. I want us to maintain a close and responsible relationship with our community. That includes maintaining a relationship with law enforcement that has made our community safe, while also preventing unnecessary non-violent arrests that can damage careers and opportunities for decades after graduation.

I want our city to look more like Ann Arbor and Madison. A community with job opportunities for graduates that extends further than joining the permanent proletariat serving class. I will continue the fight for increased urbanization, a more walkable city, a city with a safe but active nightlife, a city with interesting and fulfilling job opportunities, a city where a grocer and a pharmacy don’t demand you have a car. That’s my promise to the residents of District 1. A promise I intend to uphold until the day this privilege of a lifetime comes to an end.

Further Reading

[Ebook] The Rent Is Too Damn High: What To Do About It, And Why It Matters More Than You Think

There are two housing markets in the United States: the owner-occupied market and the rental market. Since most people live in houses they own and since renters are disproportionately poor and young, media coverage tends to treat the market for owner-occupied housing as “the” housing market. But the rental market is still a big piece of the overall economy, and unlike the owner-occupied housing market, it’s primed for a boom…

The cause of this decline in household formation isn’t mysterious: It’s the joblessness, stupid. But now that the economy’s back to creating jobs, people are going to want to get places of their own.

That’s going to mean even more demand for rental apartments at a time when vacancy rates are at their lowest level since the dot-com era. During ’90s and aughts, we consistently built fewer buildings with five units or more than were normal in the ’70s and ’80s. The country has been on a decades-long drought of large-apartment-building construction. We’re now facing a perfect storm of demand, thanks to a growing population of empty nesters with busted 401(k)s looking to downsize and the huge backlog of twentysomethings who still need their first place.

How to relieve this shortage? One possible solution is the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s new initiative to try to bundle and resell foreclosed homes as rental properties. It’s a good idea, but it has two flaws. One is that it’s not a coincidence that we normally associate renting with larger structures rather than single-family homes. The logistics of landlording are much better in multi-unit buildings. The second is that the biggest gluts of foreclosed properties aren’t where the demand for living space is. New rental housing in Phoenix, Las Vegas, or Tampa doesn’t help relieve the razor-thin vacancy rates in New York, Portland, Minneapolis, or San Jose. Only new construction will help. That’s good news for owners of existing apartments and for investors in the firms that can build new ones. Unfortunately, intrusive anti-density regulations will make it difficult to build as much or as quickly as there’s market demand for. Mayors looking to boost their local economies should move to deregulate and unleash the pent-up demand.

But even under optimal public policy, there’s no getting around the fact that apartment construction takes time. For the short term, that means rents are only going to go higher—inflicting serious pain on the poor, on young people, and on those whose credit history locks them out of the mortgage market.